Associate Teaching Professor

Carnegie Mellon University

This post is a summary of our paper, "Conversational Challenges in AI-Powered Data Science: Obstacles, Needs, and Design Opportunities". See the preprint for more details. This work was led by Bhavya Chopra at Microsoft. Special thanks to our collaborators: Ananya Singha, Anna Fariha, Sumit Gulwani, Chris Parnin, and Ashish Tiwari.

Programmers have found great value in ChatGPT, but can it do data science?

The challenges of using ChatGPT (e.g., providing context, false assumptions, and hallucinations) are made worse for data science tasks. Data scientists work with a variety of resources, like datasets, code, notebooks, visualizations, documentation, and pipelines. The data is often very large and may have quality issues. The tasks and data may require domain expertise which is tedious to fully articulate to a chat assistant. Moreover, these challenges can go both ways, as data scientists have to understand the context, data, code, and assumptions in ChatGPT's responses.

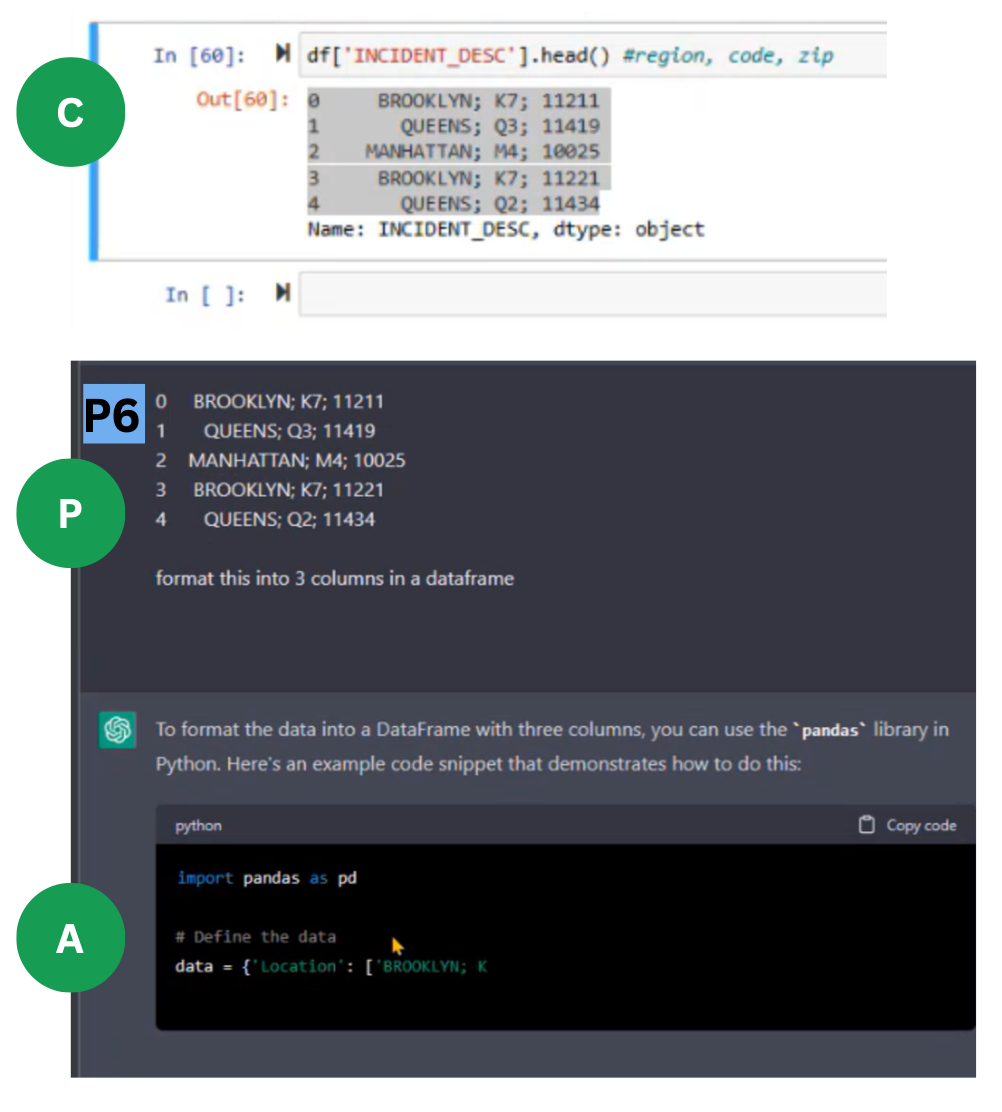

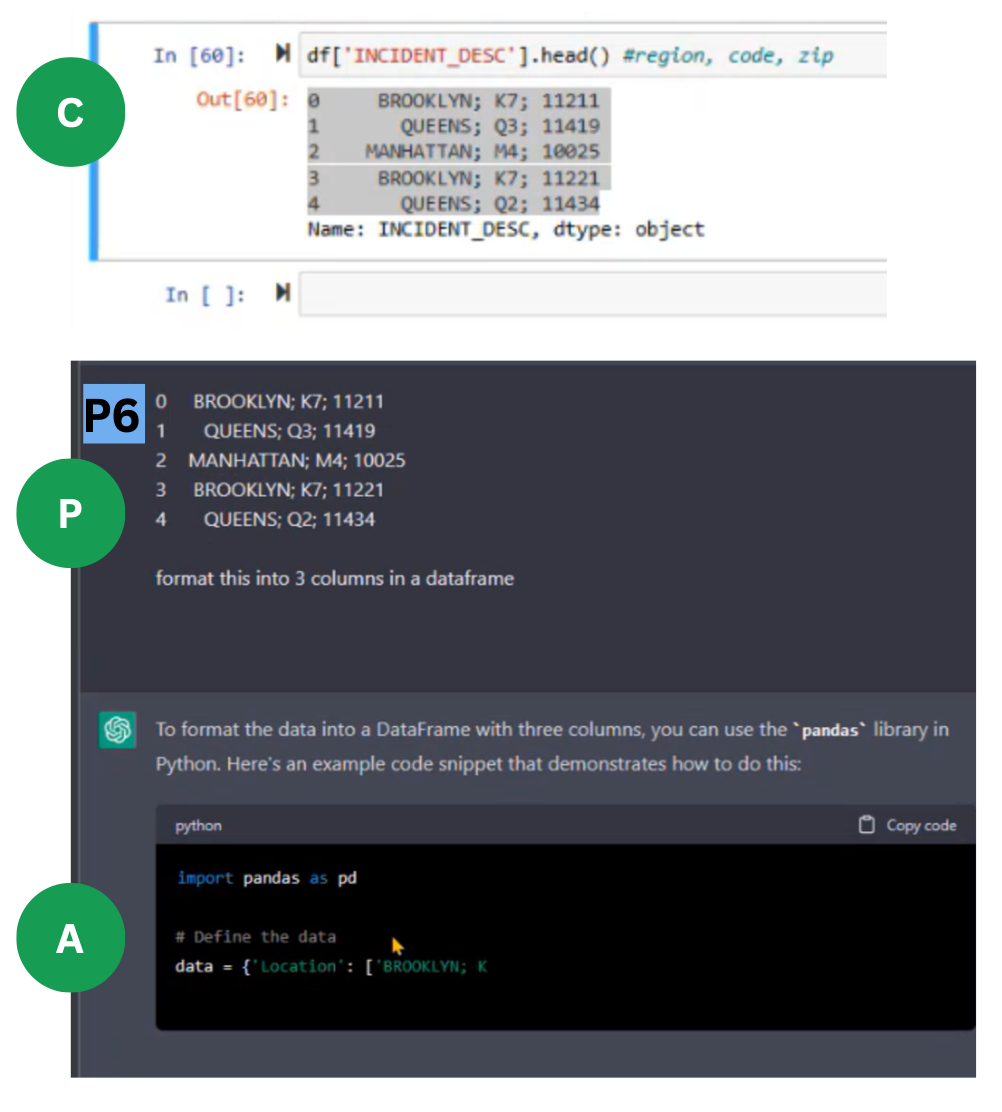

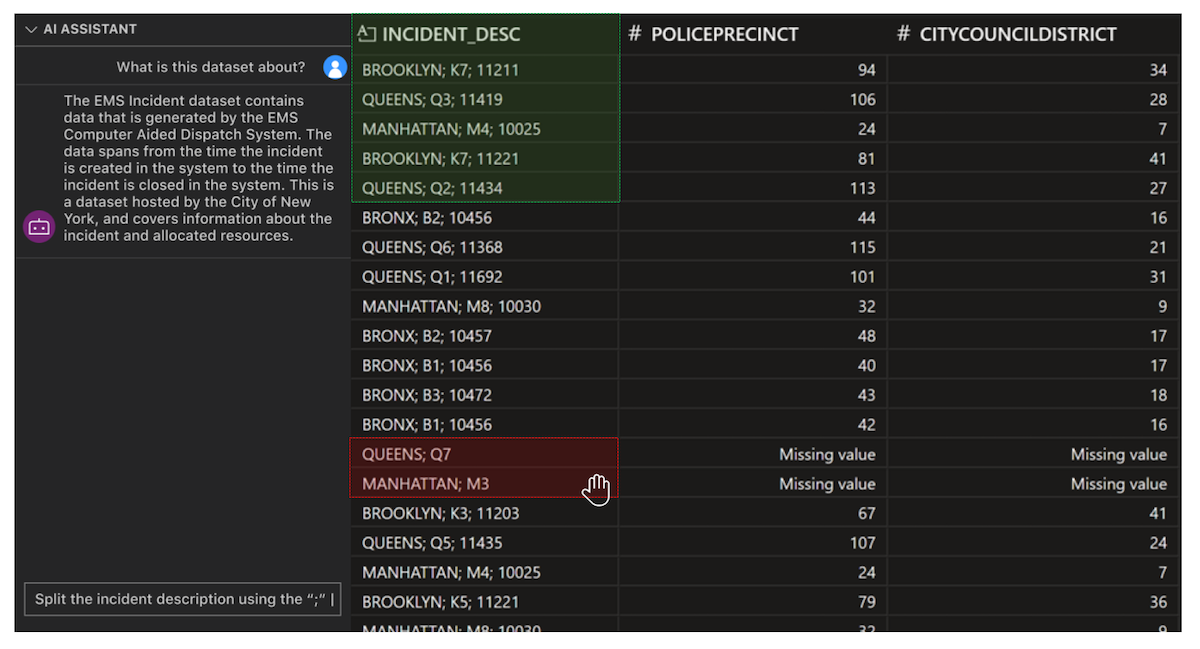

To understand how data scientists use ChatGPT and the challenges they face, we conducted two studies. In the first study, we observed 14 professional data scientists performing a series of common tasks while using ChatGPT. We avoided the use of integrated AI tools to give them complete control over prompt writing while also allowing us to study the fundamentals of interacting with AI for data science. The tasks involved type casting, splitting columns, feature selection, and plotting on the publicly available New York EMS emergency calls dataset.

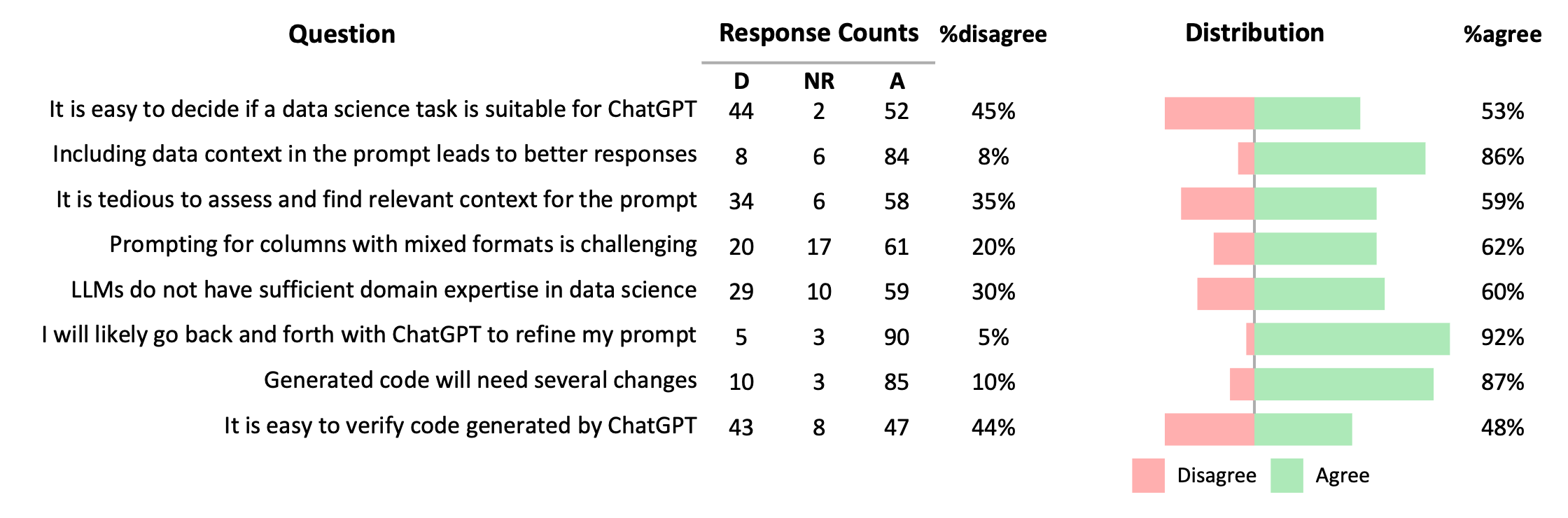

In the second study, we surveyed 114 professional data scientists to validate and generalize the findings from the observational study. We filtered out any respondents that did not have experience using LLMs for data science tasks. The survey consisted of 8 agree/disagree statements and an open-ended question.

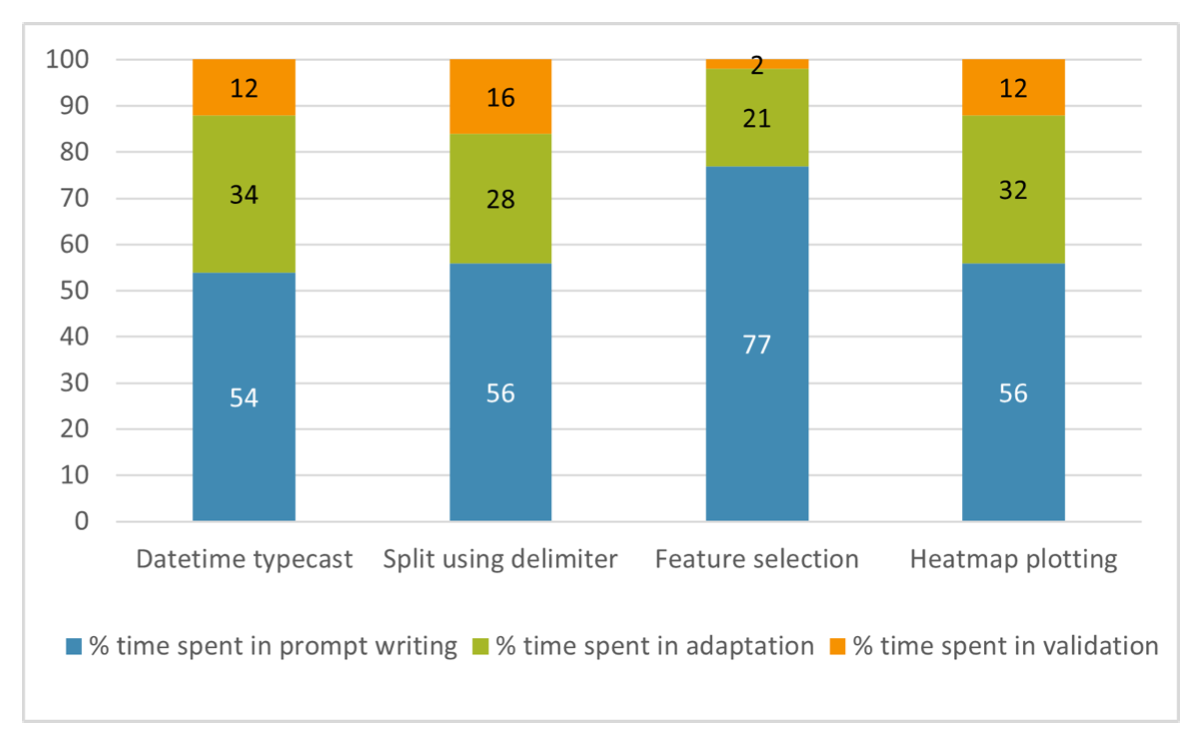

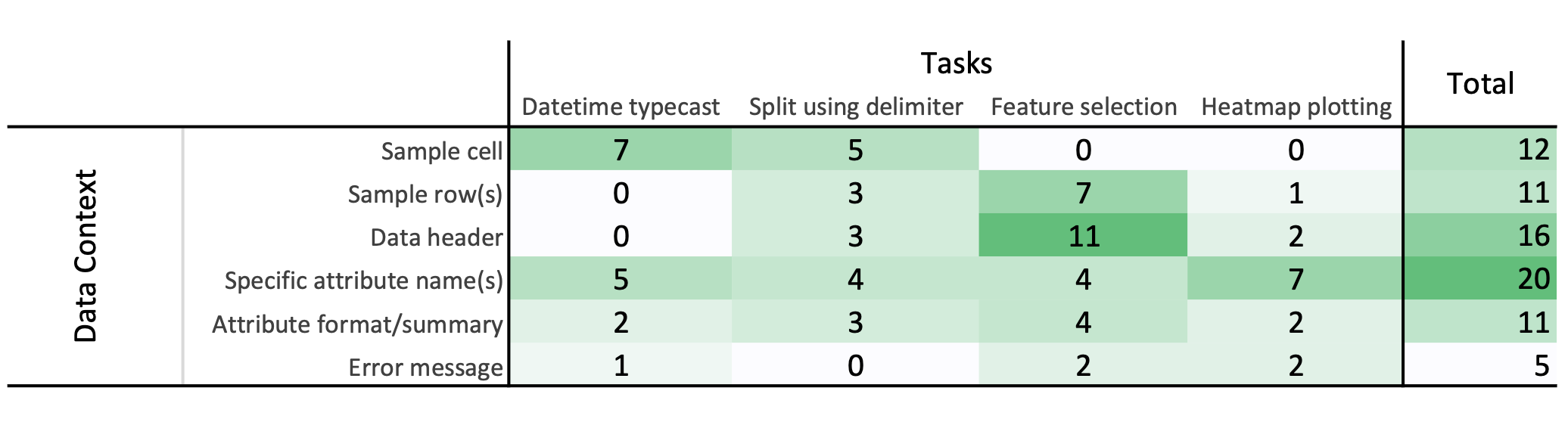

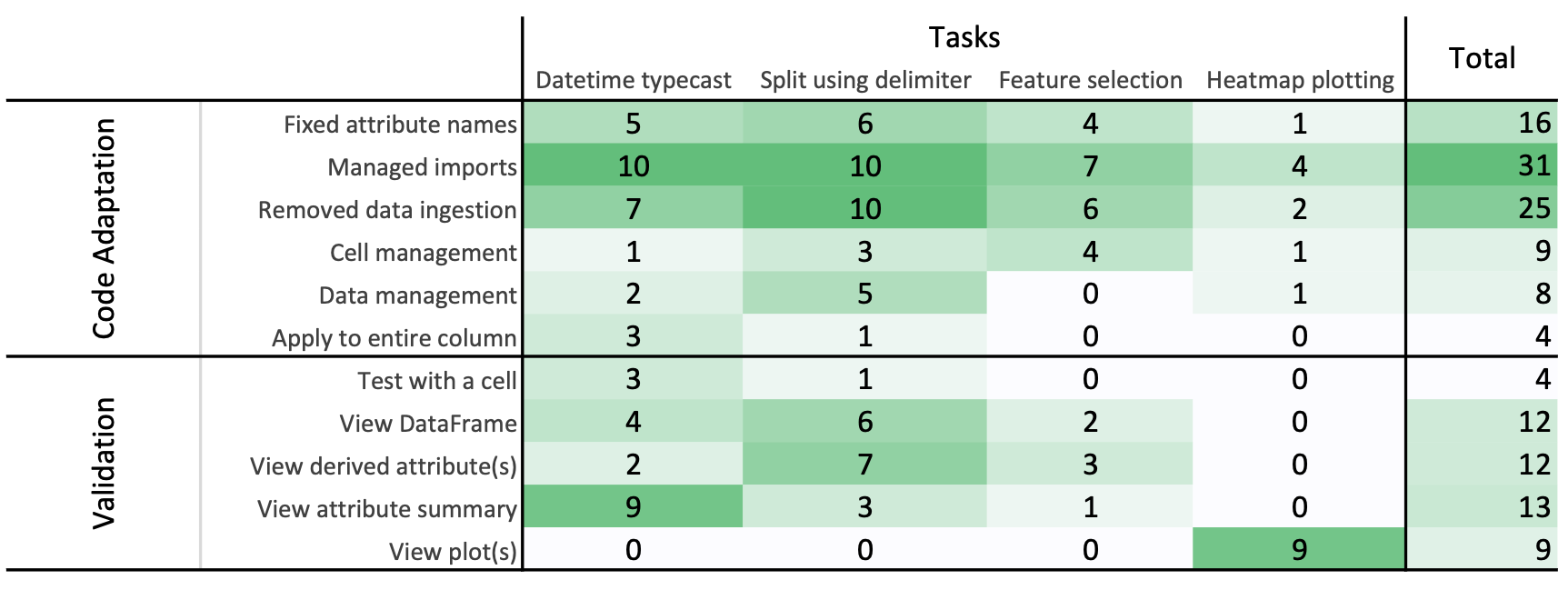

We observed the participants write 111 prompts to ChatGPT. They spent 64% of the task time preparing prompts, 27% adapting code, and the remaining time validating code. They often struggled with writing the initial prompt, especially for the feature selection task. They also iterated and refined their prompts many times, especially for the plotting task. To summarize their behavior, they all required multiple steps and the participants struggled with providing the right context to ChatGPT and then to adapt the response from ChatGPT to accomplish the task.

We observed the following challenges when participants communicated with ChatGPT:

Sharing context is difficult (10 of 14 participants). What information and how much? The data scientists begin prompt writing by figuring out which data and context they need to provide. One even called it "daunting" to get started. Some tried providing raw data, while others took elaborate steps to fetch information they deemed relevant. For example, they wrote new snippets in their notebooks to get information specifically for ChatGPT or they went to Excel to extract snippets of data. Some participants spent considerable effort reformatting information after pasting it into ChatGPT too.

ChatGPT opaquely makes assumptions (14 of 14 participants). Participants were enthusiastic about ChatGPT's ability to infer knowledge about data just from column names. However, it still made many false assumptions, including time formats, data types, and how to handle outliers. This led to some participants using code from ChatGPT that actually hid a data quality issue. One participant expressed the desire for a way to iterate on small changes faster than what is possible in the ChatGPT interface now.

Misaligned expectations (13 of 14 participants). The response that ChatGPT provides is highly temperamental to the phrasing of the prompt. For example, to include code or no code, an explanation or no explanation, one large code snippet or many small snippets, to use Pandas or another library, etc. Several participants observed that ChatGPT does not have their domain knowledge, which caused incorrect responses. They also complained of excessive explanations for straightforward portions, and we observed all participants skipping to the code.

We observed several challenges faced by participants using the code generated by ChatGPT. Recall that ChatGPT does not have direct access to their notebook, data, or other resources.

Generation of repeated code (13 of 14 participants). ChatGPT often generated redundant code, such as pandas.read_csv(). Blindly copy pasting such code would cause the participants' dataframes to be over written.

Data and notebook preferences (11 of 14 participants). The participants follow specific patterns of organizing their code, which ChatGPT did not adhere to. For example, they broke the code from ChatGPT down into small chunks and organized them as separate cells in their notebooks, sometimes in a different order than provided by ChatGPT. A few participants also refactored the generated code to not be parameterized or to not be contained within a function. Similarly, participants often modified ChatGPT's code to get the resulting data in the form they wanted (e.g., how to handle missing data and when to mutate a column versus creating a new column).

Code validation (13 of 14 participants). Many participants shared the importance of validating code from LLMs. One remarked that, "affirmative language in responses, like 'Definitely! Here's the code you need', is extremely deceiving" since it conveys a high level of confidence that was unjustified. Although participants did not spend much time verifying the code, they did employ different ways to check the correctness. They manually inspected the resulting dataframe, generated plots, checked for changes in descriptive statistics, and wrote scripts to provide further evidence.

We also observed strategies to overcome the challenges that data scientists faced:

Techniques for prompt construction (11 of 14 participants). We observed the use of one-shot prompting, few-shot prompting, chain of thought prompting, and asking ChatGPT to assume the rule of an expert. They also wrote prompt templates to reduce context switching between ChatGPT and their notebook or spreadsheet.

Scaffolding with domain expertise (3 of 14 participants). Participants were cautious of ChatGPT's "understanding" of their data, though we only observed a handful of cases where they attempted to use their own domain expertise to successfully guide ChatGPT. For example, one participant wanted to avoid ChatGPT using any of the time data so they omitted columns that contained 'TIME' or 'ID' in them from the prompt. Another participant did something similar by filtering the columns to those that were of type 'float' first.

Choosing an alternative resource (6 of 14 participants). Participants shared reasons why ChatGPT may not be appropriate for their work. Three participants asked about data sharing and privacy for ChatGPT. Other participants said that writing code for processing new data sets is relatively rare, since they often rerun their existing pipelines on new batches of data in the same structure. A few did remark that using LLMs help them save time over performing web searches.

The survey results can be seen below. It looks to be a coin toss for whether data scientists know if a task is suitable for ChatGPT or not. They strongly agree that they should include data in their prompt, it will require multiple back and forths with ChatGPT, and the code will require changes.

From our studies and the related work, we make three recommendations for the design of AI-powered data science tools:

Provide preemptive and fluid context when interacting with AI assistants. Participants spent considerable time writing their prompts and gathering context. In fact, 45% of the prompts included data that was manually entered or required additional scripts to obtain. Additional interfaces are needed to enable data scientists to efficiently select and manage context. For example, what if you could select regions of the screen to include or exclude as context?

Provide inquisitive feedback loops and validation-aware operations. For open-ended or complex tasks, it can take many interactions with ChatGPT to get to a satisfactory result. Instead of this back-and-forth conversation instigated by the user, the system could guide the user throughout the task and proactively ask clarifying questions.

Provide transparency about shared context and domain expertise solutions. It can be difficult to know what context is needed and what assumptions are being made. There needs to be mechanisms for more efficient sharing of context that goes both ways between the data scientist and the AI. A possible interface for this could be a separate pane that maintains an updated list of assumptions that can be modified at any time.