Associate Teaching Professor

Carnegie Mellon University

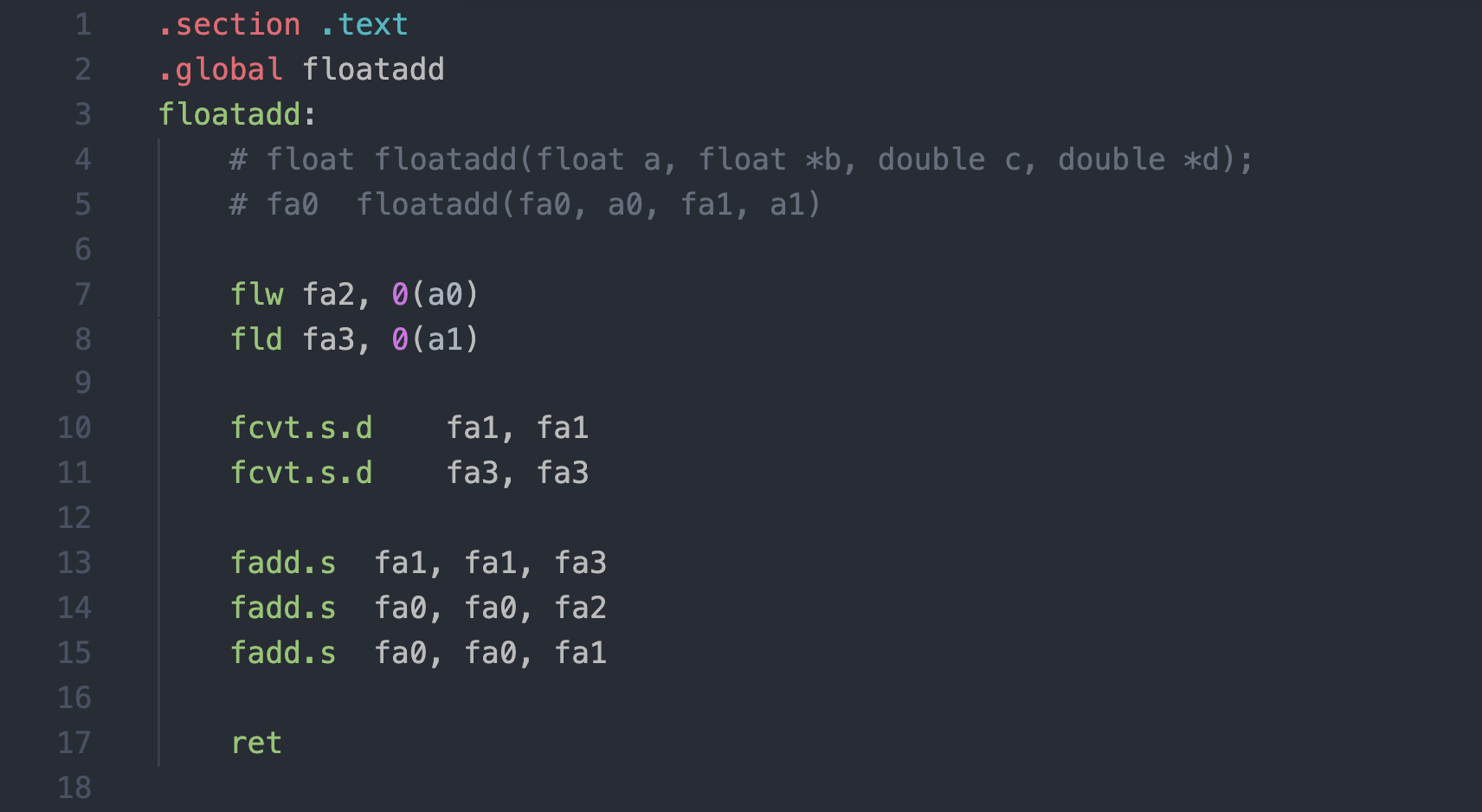

Recently, I needed to analyze some RISC-V assembly code for a research project and then calculate some basic metrics, but I couldn't find a suitable tool. Ok, I'll just grab a parser from one of the smaller open-source assemblers. This wasn't successful though since the ones I looked at use crude, regex-based parsers that don't maintain information about the structure.

Not a problem, I'll implement my own! Let me just look up the grammar for RISC-V assembly... oh no, there isn't an official one?! Wait. The language itself isn't even standardized beyond the instruction set, and each major assembler supports different notations and features???

Challenge accepted! My goal is to write a parser that supports the GNU assembler's (GAS) syntax.

If you are looking for a hand-written lexer and parser for RISC-V assembly that builds a parse tree and does not have any third-party dependencies (e.g., ANTLR or Yacc), then this is for you. It could be handy in making your own linter, prettifier, or assembler for RISC-V. Alternatively, if you want a more in-depth tutorial on parsing, see the first part of my tutorial series: Let's make a Teeny Tiny compiler.

The source code for the parser can be found on GitHub. If you want to know more about RISC-V assembly, see my colleague's lecture notes.

The core of most assembly languages is beautifully simple. A source file is composed of zero or more labels, instructions, directives, and comments. We can represent it in EBNF like so:

program ::= {label | instruction | directive | comment}

Such a language would be very easy to parse. At the start of each line, decide whether it is a label, an instruction, a directive, or a comment. Let's keep going with this and expand these terms:

program ::= {label | instruction | directive | comment}

label ::= symbol ':'

instruction ::= symbol [symbol {',' symbol}]

directive ::= '.' symbol [symbol {',' symbol}]

Label is simple enough. An instruction is a symbol followed by zero or more operands that are comma separated. Here I am using symbol as a catch all. It can be a number, a register, an instruction, or a label. A directive is essentially the same as an instruction but it starts with a period.

Are we ready to implement the parser yet? Not quite. Although this is almost enough for RISC-V assembly, it is still missing quite a few features. To name a few: labels can be on the same line as an instruction, values can have a leading positive or negative sign, and offsets can be specified for an operand.

Here is the full grammar and lexing rules I came up with for RISC-V:

program ::= {[label] [directive | instruction] [comment] newline}

label ::= symbol ':'

directive ::= '.' symbol [['.' | '+' | '-'] symbol {',' ['+' | '-'] symbol}]

instruction ::= symbol [operand {',' operand}]

operand ::= ['+' | '-'] (symbol '(' symbol ')' | symbol)

# Lexer rules in regex-ish notation.

newline ::= [\n\r]+

comment ::= #[^\n\r]+

symbol ::= ([a-zA-Z0-9]('.'?[a-zA-Z0-9])*) | (\"(\\[^\n]|[^"\n])*\")

# Whitespace, commas, colons, and parentheses are token delimiters.

# Spaces and tabs can be used interchangeably and consecutively.

But wait! How do we know that an instruction or register was used properly? I decided to keep the grammar as minimal as possible and to verify such things later on. That means that this grammar will accept some code that is not allowed, but that in the next step we can prune out. For example, "xor xor, xor, xor, xor" will be parsed just fine, despite it not being legal RISC-V assembly. We can fix that.

If you are interested in using the parser for your own project, there may be a few things you'll want to add. Namely, a verification step, similar to a semantic analysis step in compilers, that checks some of the following things:

You would check these in the parser, by modifying the grammar functions, Label(), Directive(), Instruction(), and Operand(), to check the contents of the tokens.

As an example, let's take a look at the parsing code for instructions:

void Parser::Instruction() {

NextToken();

// Is there at least one operand?

if(!CheckToken(TokenType::Newline) && !CheckToken(TokenType::Comment)) {

Operand();

// Zero or more operands.

while(CheckToken(TokenType::Comma)) {

NextToken();

Operand();

}

}

}

Now I'll add some fictitious function calls showing how a possible verifier could work:

void Parser::Instruction() {

int numOperands = verifier->LookupInstruction(token->literal);

if(numOperands == -1) {

ReportError("Invalid instruction.");

}

NextToken();

// Is there at least one operand?

int actNumOperands = 0;

if(!CheckToken(TokenType::Newline) && !CheckToken(TokenType::Comment)) {

Operand();

actNumOperands++;

// Zero or more operands.

while(CheckToken(TokenType::Comma)) {

NextToken();

Operand();

actNumOperands++;

}

// Verify correct number of operands.

if(numOperands != actNumOperands) {

ReportError("Incorrect number of operands.");

}

}

}

Voila! The instructions and number of operands are now verified. To actually do this, I recommend implementing a Verifier class that has functions for looking up if an instruction/directive exists and the number and format of operands for each, along with functions for verifying literals, registers, and labels.

Similarly, you can add an emitter step if you were building an assembler. In this scenario, you would look up the corresponding binary representation of each instruction and operand, emitting those to a file as you parse. You can see how a compiler does this in the emitting portion of my Let's make a Teeny Tiny compiler tutorial.

A notable feature that cannot be parsed with this parser is math expressions. Luckily, this is a fairly easy thing to add! I have previously written a tutorial on parsing that covers math expressions. See part 1 of Let's make a Teeny Tiny compiler. The GNU assembler supports two prefix operators, - and ~ for negation and complementation, and these binary operators from highest precedence to lowest: *, /, %, <, <<, >, >>, |, &, ^, !, +, -.

To support math expressions, you can expand the grammar from above with something like:

expression ::= bitwise {( "-" | "+" ) bitwise}

bitwise ::= term {( '|' | '&' |'^' ) term}

term ::= unary {( "/" | "*" ) unary}

unary ::= ["+" | "-"] symbol

Preprocessor features (i.e., #include and #define) and multi-line comments are left as an exercise to the reader... 🙂

The core of assemblers really are quite simple. They do little more than string substitution, so parsing should be trivial. Assembly languages aren't even recursive! You just need to replace instruction mnemonics and operands with their respective binary representation. However, the mainstream assemblers allow constructs that make parsing a little more complicated, plus assembly languages are not standardized. Despite all this, this article should prove that these problems can be solved if you take them step by step.

Hopefully this parser can help you with your RISC-V project. If you use it, shoot me an email and let me know about your project! You can find the source code on GitHub.